By Bryce P Wandrey

This essay was originally published in the Spring 2010 issue of Lutheran Forum.

This past year I was caught off guard in conversation with a fellow curate in London. He was a former Reformed minister who had been ordained into the Church of England. I had served the Lutheran Church-Missouri Synod for four years as a minister, but I too have been ordained into the Church of England. In the midst of our conversation, on learning that I had a Lutheran background, my conversation partner related to me what had once happened when he presented himself for reception of the sacrament of the altar at a Lutheran church. He said in astonishment, “I was asked if I would be willing to sign (not literally) the Augsburg Confession before receiving. I just wanted communion.”

This story raises the age-old question (at least since the Last Supper itself): who should be welcomed to the table? Who should be “allowed” to partake in the eucharist at a given altar? Most Christian denominations have pretty clear-cut, if not always easy to interpret or implement, answers to these questions. Traditionally, baptism in the name of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit is a “requirement” for admittance to the holy supper. The logic typically runs that baptism is the sacrament that “makes” a Christian, initiating the recipient into the church and bestowing the everlasting benefits of Christ’s death and resurrection. But assuming the baptized person’s status as a full member of the church, how do we decide which members of the ecclesial community may worthily and rightly receive the sacrament of the altar? Which criteria are the necessary ones for giving a Christian the church’s meal?

For example, some communions require confirmation in order to receive the sacrament, though not all do. Those that do require confirmation do not necessarily believe that the rite of confirmation itself bestows worthiness upon the recipient to receive communion. And yet in this case the affirmation of faith, which is an integral part of the confirmation process, is a requirement for worthy reception of the sacrament of the altar, even if it isn’t meant to be. Confirmation is but one instance among many of ways of acertaining the “worthiness” of the recipient. What follows is an attempt to understand what Martin Luther intended as criteria for worthy reception, not to address any one specific communion policy in Christendom but with the hope that Luther’s criteria can address, confront, and challenge all the requirements of all communion policies across the board.

To begin with, in the papal bull Exsurge Domine, which condemned forty-one articles of Luther’s public teaching, the fifteenth article states Luther’s own position thus: “They are greatly in error who, when communing, rely on the fact that they have confessed, or that they are not aware of any mortal sin and have said their prayers. But if they believe and trust that in the sacrament they receive grace, this faith alone makes them pure and worthy.”[i] If one believes and trusts that in the sacrament she will receive grace, Luther teaches, then her faith alone makes her worthy to receive.

Luther’s contemporary application of this statement, as outlined in his “Defense and Explanation of All the Articles (1521)”, is directed at those “of timid conscience, who prepare themselves for the sacrament with much worry and woe and yet have no peace and do not know how they stand with God.”[ii] To those driven to doubt their own worthiness, based as it is upon their “deficient” contrition or confession, Luther gives these words of comfort: “Faith alone must always be the proper cleansing and worthy preparation.”[iii] Luther constantly spoke of justification by faith alone. Here we see that worthy reception of the sacrament is based upon just that same disposition towards God: faith alone.

It might be helpful to consider what Luther means when he uses the word “faith.” At the heart of the matter is the definition of faith as fiducia, “trust,” in opposition to other conceptions of faith as fides, “belief/cognition.” In his Defense, Luther writes:

For it is not possible for a heart to be at peace unless it trusts in God and not in its own works, efforts, and prayers. St. Paul says in Rom. 5[:1], “By faith we have peace with God.” But if peace comes only through faith, it cannot be achieved through works, prayers, or anything else. Experience also teaches that even though a man may work himself to death, his heart has no peace until he begins to yield himself to God’s grace, and takes the risk of trust in it.[iv]

There are two accounts of faith, faith as fiducia and faith as fides, which includes cognitively holding something to be true. Bernhard Lohse aptly summarizes Luther’s distinction: “Reason denotes the capacity for knowledge… Faith, on the other hand, is a matter of the ‘heart.’ It concerns chiefly one’s relation to God under the perspective of judgment and grace… In the midst of inner conflict caused by the threat of divine judgment, faith means to trust in God’s promise of grace… In faith, trusting in God alone, we let God be God.”[v] More statements like this could be culled from both Luther’s works and his commentators, but the picture is clear: faith is trust in God and in His promises, refocusing our trust away from ourselves and solely on God.

In the context of the question of whether we are worthy to receive the sacrament, faith alone deflects away from ourselves to another, to God and His righteousness. It is His alien righteousness that makes us worthy, because we approach the sacrament trusting in God and not in ourselves, not having faith in our “works, prayers, or anything else.”

What Luther definitely wants to exclude is any kind of human work when it comes to determining one’s worthiness to receive the sacrament. Logically, this means both mental works (confession, contrition, understanding, etc.) and physical works (pilgrimage, tithes, etc.) that give people a presumption of worthiness based upon their own efforts. Oswald Bayer reflects on this aspect of Luther’s conception of faith when he writes, “The moment we turn aside and look back at ourselves and our own doings instead of at God and God’s promise, at that moment we are again left alone with ourselves and with our own judgment about ourselves. We will then be inevitably entangled in ourselves. We will fall back into all the uncertainty of the defiant and despairing heart that looks only to self and not to the promise of God.”[vi] Faith is not a person’s work, something that the person can achieve and then boast about. Faith is a relationship with God, letting go of oneself and grasping instead God who acts on one’s behalf.

Returning now to the “Defense,” we find Luther reflecting upon the words of St. Paul in 1 Corinthians 11:28, “Let a man examine himself, and so eat of the bread and drink of the cup.” He writes: “They have interpreted this saying to mean that we should examine our consciences for sin, although it means rather that we should examine ourselves for faith and trust, since no man can discover all his mortal sins.”[vii] Instead of human efforts to prepare ourselves, instead of directing our focus inward, what is absolutely necessary for a worthy reception of the sacrament is faith: trust that the sacrament was given and shed “for you,” believing that in the sacrament we will receive God’s grace. Luther’s counsel in the “Defense” can be summarized as such: let no one drive you back to your own works, either mental or physical, to give you consolation that the sacrament is for you. Instead look to the words of Christ: given for you, shed for you. “I wish we would be driven away from works and into faith, for the works will surely follow faith, but faith never follows works.”[viii]

These works of which Luther speaks (and the consequent theology of faith alone), while they were most directly in reference to tasks such as penance, must be applied more widely today, to those “requirements” demanded of prospective communicants. And hence, is it not be a “work” of preparation (at least in some respect) to get one’s doctrine “up to par” or to “sign” a document in order to receive the sacrament? Is this not an example of blurring trust and cognition, of confusing faith and reason, of exchanging fiducia for fides? How much latitude can we allow in defining the “faith” in “faith alone”? Luther, I believe, would allow no such latitude: faith must be restricted to trust in God, trust in God’s promises.

Another instance of Luther explicating his understanding of worthiness in regard to receiving the sacrament came in March of 1521 when he wrote a “Sermon on the Worthy Reception of the Sacrament.”[ix] He began by stating that those who are living openly in sin shall not receive the sacrament.[x] He then proceeded to the two main points in his sermon (to which he returns throughout): 1) No one should come to the sacrament because he feels compelled to by law or command; 2) Only she who feels a great hunger and thirst for God’s grace should come to the sacrament.

Hunger and thirst, not compulsion, are necessary for a worthy reception of the body and blood of Christ. “There must be hunger and thirst for this food and drink; otherwise harm is sure to follow.”[xi] The beginning of such hunger leading to a worthy reception is “[t]o know and understand your sin and to be willing to get rid of such vice and evil and to long to become pure, modest, gentle, mild, humble, believing, loving, etc.”[xii]

Those who trust in their own worthiness should avoid coming to the sacrament. Here Luther combines a rejection of a false humility when approaching the sacrament with faith in Christ’s words. The focus is shifted away from the worthiness of the believer and instead to that which he believes: Christ and his words, most notably his words instituting the sacrament. “[E]very Christian should have these words close to himself and put his mind on them above all others.”[xiii] This is an obvious echo of Luther’s understanding of faith itself, here applied to a worthy reception of the sacrament of the altar, which centers a person’s gravity away from herself and on to another, namely Christ.

Luther is adamant that in order to receive the sacrament worthily we should never rely upon our own diligence or effort, work or prayers, fasting or other outward preparations, but instead should rely solely upon “the truth of the divine words.”[xiv] When we are driven to our own purity we are led down the wrong path, made shy and timid, and the sacrament is reduced from being a sweet and blessed thing to a “frightful and hazardous act.”[xv] Luther quips, “If you do not want to come to the sacrament until you are perfectly clean and whole, it would be better for you to remain away entirely,”[xvi] words echoed in his Large Catechism: “If you choose to fix your eye on how good and pure you are, to wait until nothing torments you, you will never go.”[xvii] Instead of a misguided purity, what is necessary is trust in the perfection of God’s righteousness, not our own.

Luther concludes his sermon by writing that “[t]he only question is whether you thoroughly recognize and feel your labor and your burden and that you yourself fervently desire to be relieved of these. Then you are indeed worthy of the sacrament. If you believe, the sacrament gives you everything you need.”[xviii] One should not commune in either open sin or under compulsion, but instead a worthy recipient of our Lord’s body and blood in the sacrament is that person burdened by their sin and hungering for God’s grace. In other words: the worthy recipient is that person who clings to Christ alone with faith alone.

This theology of grace is contained nicely in a prayer of preparation for the sacrament that Luther includes in the sermon.

Lord, it is true that I am not worthy for you to come under my roof, but I need and desire your help and grace to make me godly. I now come to you, trusting only in the wonderful words I just heard, with which you invite me to your table and promise me, the unworthy one, forgiveness of all my sins through your body and blood if I eat and drink them in this sacrament. Amen.

Dear Lord, I do not doubt the truth of your words. Trusting them, I eat and I drink with you. Do unto me according to your words. Amen.[xix]

The emphasis upon trust only in the words of invitation to receive the sacrament, trust in the grace of God offered in the sacrament, trust in God and not oneself, is unmistakable.

Once more, on 14 March 1522, Luther took up the issue of worthily receiving the sacrament of the altar in a sermon, this time on the Friday after Invocavit Sunday.[xx] He begins by distinguishing between an outward reception of the sacrament and an inner (spiritual) reception. It is by an outward reception that a person receives, with their mouth, the body and blood of Christ in the sacrament. Luther affirms that any person can receive the sacrament in this manner but without faith and love this outward reception does not “make a man a Christian.”[xxi] Hence, there must be faith to make the reception of the sacrament “worthy and acceptable” before God. “Christianity consists solely in faith, and no outward work must be attached to it.”[xxii]

Luther then helpfully defines faith for us when he writes, “But faith (which we all must have, if we wish to go to the sacrament worthily) is a firm trust that Christ, the Son of God, stands in our place and has taken all our sins upon his shoulders and that he is the eternal satisfaction for our sin and reconciles us with God the Father.”[xxiii] Faith for Luther, as illustrated earlier in this essay, is simply a trust that Christ has accomplished the unified act of bearing our sins, making satisfaction for our sins, and reconciling us with his Father. It is trust that God has “stepped in” for us and taken our place and offered his blood on our behalf.[xxiv] Faith is a shift in focus away from ourselves and on to Christ. And now, here in this sacrament, Christ offers his body and blood to us “as an assurance, or seal, or sign to assure [us] of God’s promise and grace.”[xxv] Finally, Luther echoes the same criteria that he laid down in his 1521 sermon when he writes, “This food demands a hungering and longing man, for it delights to enter a hungry soul, which is constantly battling with its sins and eager to be rid of them.”[xxvi]

We now come to the Small and Large Catechisms (1529), both foundational and instrumental documents for Luther’s theology. The “Small Catechism” states that the sacrament is “the true body and blood of our Lord Jesus Christ, under the bread and wine, given to us Christians to eat and drink.”[xxvii] Here we encounter, in a slightly implicit way, the “requirement” of belief in the “real presence” of the body and blood of Christ in the sacrament, something that is more explicitly stated in other writings of Luther’s. Earlier in his life Luther wrote in “Against the Heavenly Prophets”: “But I do know full well that the Word of God cannot lie, and it says that the body and blood of Christ are in the sacrament.”[xxviii] Luther’s requirement of this understanding of the “presence” of Christ in the sacrament becomes only too explicit in his adamant disagreement with Zwingli at the Marburg Colloquy, as Lohse highlights, “[O]ne may say that Luther’s Reformation theology took on particularly significant shape in the debate with Zwingli over the Supper.”[xxix] As a result, Luther said he would rather drink the blood of Christ with the pope than drink mere wine with “the fanatics,”[xxx] which lends weight to the “requirement” of recognizing Christ’s body and blood as present in the sacrament for a worthy reception.

In his “Large Catechism,” Luther once more addresses head on who should partake of the sacrament. “It is the one who believes what the words say and what they give, for they are not spoken or preached to stone and wood but to those who hear them, those to whom he says, ‘Take and eat,’ etc. And because he offers and promises forgiveness of sins, it can be received in no other way than by faith.”[xxxi] Interestingly, if Luther here pushes faith beyond simple trust and invokes a sense of “belief in” something, he does so only in reference to the focus or object of the words of institution. He writes, “This faith he himself demands in the Word when he says, ‘given for you and ‘shed for you,’ as if he said, ‘This is why I give it and bid you eat and drink, that you may take it as your own and enjoy it.’ All those who let these words be addressed to them and believe that they are true have what the words declare.”[xxxii] While it is possible that Luther here requires faith in the fides sense for a worthy reception, it is equally possible, based upon the for you-ness of Christ’s words, that Luther is actually requiring the fiducia sense of faith as looking away from oneself and to Christ.

This still begs the question: by insisting upon a certain element of “right belief” (a “right belief” of the presence of Christ in the sacrament) for a worthy reception of the sacrament, has Luther introduced an element that breaks asunder his “faith alone” criteria? No. As illustrated from the “Large Catechism,” that to which Luther directs a person’s attention in recognizing the mode of Christ’s presence in the sacrament is not his works nor his intellect but once again the promises of God and nothing else. That means: not a person’s worthiness, not even her doctrinal fidelity. Here we cannot allow the entrance of a doctrinal-faith dialectic when it comes to “faith worthiness” and the sacrament. This is because what Luther emphasizes is not a person’s worthiness as evidenced in his “right belief” but instead, once again, a trust in God’s word and promises. Luther’s main focus and emphasis in insisting upon “belief” in a certain mode of presence in the sacrament was not a case of believing in a right concept but instead trusting the words of Christ; once again, fiducia and not fides. In other words, Luther’s insistence on the real presence in the sacrament is not a fides addition required of the communicant but instead a logical application or outworking of his faith (=fiducia) alone principle.

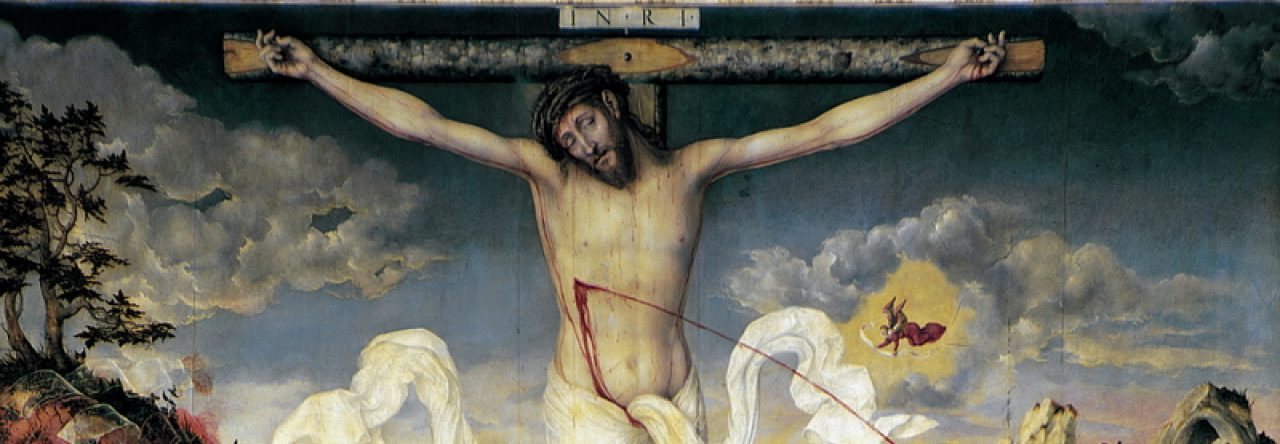

Luther’s concern was to not make God out to be a liar, but to allow God’s words to speak, to be heard and trusted. Ultimately, it was an effort to free a Christian from any complex extra-biblical understanding of how Christ was present and to allow the clear words of institution to stand alone. One can quibble with Luther’s understanding of Christ’s mode of presence in the sacrament on the basis of the verba, but one cannot use his insistence upon the “real presence” of Christ in the sacrament to introduce the aforementioned “doctrinal-faith” element. As Lohse emphasizes, “As to the significance of the words of institution, from his early period onward Luther was concerned with a complex but materially necessary connection between Christ’s establishing or instituting the Supper, the sign of presence of the crucified and risen Lord under the bread and wine, and the meaning or promise as apprehended in faith.”[xxxiii]

Who worthily receives the sacrament? She who can intellectually assent to a set of doctrines and “sign on”? Or she who says, “I just want communion”? I think we can answer, based upon Luther’s theology, that the first requires too much, and is in fact a corruption of Luther’s understanding of faith as fiducia, while the latter, which is on the right track, needs more—but not much more.

Luther lays out three criteria for worthily receiving the sacrament of the altar over the breadth of his theological writings. He is worthy to receive the sacrament who 1) has faith[xxxiv] in Christ alone, 2) hungers for the sacrament as a means of receiving God’s grace, and 3) recognizes Christ’s body and blood in the sacrament under the elements of bread and wine, because that person trusts Christ’s words, “This is my body, this is my blood.” These are the criteria that should determine entrance to the sacrament of the altar (definitely no more but also no less), criteria that, yes, the church should insist upon, but more importantly, criteria that the baptized individual should use as a means to examine herself. And yet here we tread the slippery slope of promoting “self-examination” as a criterion, an exercise toward “worthy reception.” At times it is best to say little, only what is absolutely necessary, and leave it at that: “For the worthy reception, faith is necessary, by which one firmly believes Christ’s promise of remission of sins and eternal life, as the words in the sacrament clearly state.”[xxxv]

[i] Luther’s Works, American Edition, 55 vols., eds. J. Pelikan and H. Lehmann (St. Louis and Philadelphia: Concordia and Fortress, 1955ff.), 32:54 [hereafter cited as lw].

[ii] Ibid.

[iii] lw 32:55.

[iv] lw 32:54. My italics.

[v] Bernhard Lohse, Martin Luther’s Theology: Its Historical and Systematic Development (Minneapolis: Fortress, 1999), 201.

[vi] Oswald Bayer, Living by Faith: Justification and Sanctification (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2003), 44.

[vii] lw 32:55. My italics.

[viii] Ibid.

[ix] Martin Luther, “Sermon on the Worthy Reception of the Sacrament,” lw 42:170–77.

[x] lw 42:171.

[xi] lw 42:172.

[xii] Ibid.

[xiii] lw 42:173.

[xiv] lw 42:174.

[xv] lw 42:175.

[xvi] Ibid.

[xvii] Martin Luther, “Large Catechism,” in The Book of Concord, eds. Robert Kolb and Timothy J. Wengert (Minneapolis: Augsburg Fortress, 2001), v.57.

[xviii] lw 42:177.

[xix] lw 42:174.

[xx] lw 51:92.

[xxi] Ibid.

[xxii] Ibid.

[xxiii] Ibid. My italics.

[xxiv] lw 51:93.

[xxv] Ibid.

[xxvi] lw 51:94.

[xxvii] Martin Luther, “Small Catechism,” in The Book of Concord, iv.2.

[xxviii] lw 40:176.

[xxix] Lohse, 306.

[xxx] lw 37:317: “Against this someone will object once more, ‘But you yourself declare that the wine remains wine in the new Supper. These words of yours make you a good papist who believes that there is no wine in the Supper.’ I reply: This bothers me very little, for I have often enough asserted that I do not argue whether the wine remains wine or not. It is enough for me that Christ’s blood is present; let it be with the wine as God wills. Sooner than have mere wine with the fanatics, I would agree with the pope that there is only blood.”

[xxxi] “Large Catechism,” v.33–34.

[xxxii] Ibid.

[xxxiii] Lohse, 306–7. My italics.

[xxxiv] Importantly, this is faith defined as trust in God as “for us” and not faith achieved or proven on the battle grounds of “right belief.” In other words, as shown throughout this essay, it is faith defined as fiducia and not fides.

[xxxv] lw 34:355.