By Dr Mark Mattes

Defining the Protestant View of Justification

The Lutheran understanding of justification, developed in contrast with the late medieval theologians, is most concisely stated and summarized in article IV of the Augsburg Confession (1530), written by Philip Melanchthon (with Luther’s endorsement):

“Furthermore, it is taught that we cannot obtain forgiveness of sin and righteousness before God through our merit, work, or satisfactions, but that we receive forgiveness of sin and become righteous before God out of grace for Christ’s sake through faith when we believe that Christ has suffered for us and that for his sake our sin is forgiven and righteousness and eternal life are given to us. For God will regard and reckon this faith as righteousness in his sight, as St. Paul says in Romans 3[:21-26] and 4[:5]” (Book of Concord, 38:1-40:3).

In distinct opposition to the perspectives of late antiquity and the middle ages what stands out in this statement is that justification is decisively forensic, a decree of acquittal, as opposed to something God does in order to initiate a process on the ladder of ontological, moral, and mystical fulfillment. Likewise, faith is not to be understood as a “theological virtue,” but as a state of being grasped by God’s unconditional claim and promise. Grace is not the power behind the scenes initiating our process in mimetic growth but the very pronouncement of forgiveness itself. Therefore, it is faith, not love that saves. Abraham trusted God’s promise, and it was reckoned to him as righteousness, since “the righteous shall live by faith” (Habakkuk 2:4).

In distinct opposition to the perspectives of late antiquity and the middle ages what stands out in this statement is that justification is decisively forensic, a decree of acquittal, as opposed to something God does in order to initiate a process on the ladder of ontological, moral, and mystical fulfillment. Likewise, faith is not to be understood as a “theological virtue,” but as a state of being grasped by God’s unconditional claim and promise. Grace is not the power behind the scenes initiating our process in mimetic growth but the very pronouncement of forgiveness itself. Therefore, it is faith, not love that saves. Abraham trusted God’s promise, and it was reckoned to him as righteousness, since “the righteous shall live by faith” (Habakkuk 2:4).

The Inner Logic of Imputation

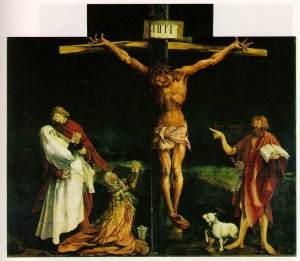

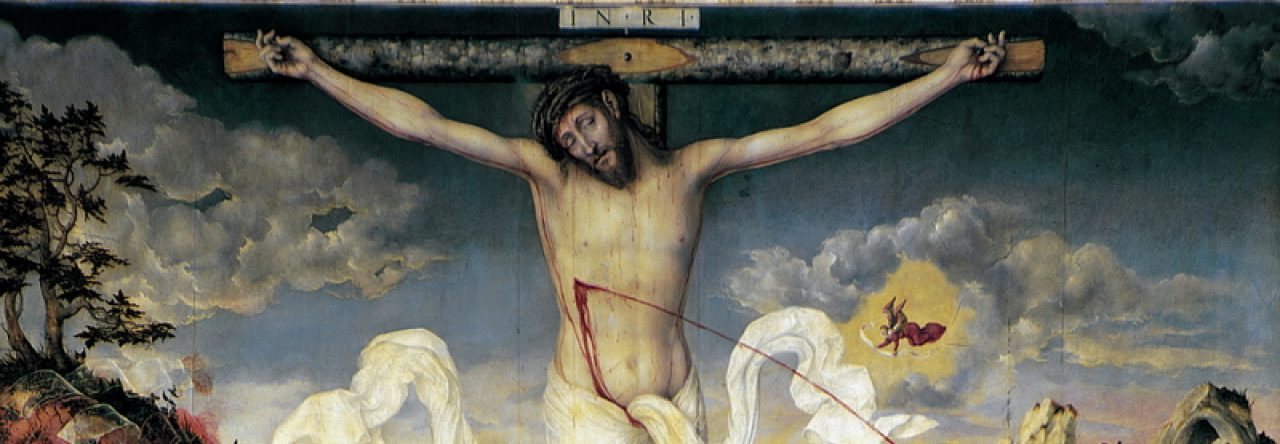

Evangelical reformers and medieval thinkers both used the same terminology about justification, but the Lutheran perspective entirely subverts the inner logic of the ladder. Hidden behind article IV of the Augsburg Confession is much theological spade work done by Luther prior to his evangelical breakthrough. For lack of a better term, the “logic” behind the Lutheran perspective is decidedly “eschatological.” What this means is that God’s judgment on all humanity which will be rendered on the Last Day has already been rendered in time, in a specific act, that of the death and resurrection of his Son, Jesus Christ, and is conveyed to the world through the words of a preacher. It is on the basis of God’s own vindication of his Son, who was himself without sin, but became sin for us and so was in the end justly accused as a violator of the Torah–God’s own law–that all sinners can have assurance of eternal life. In violating the law, Jesus Christ was faithful to his Father’s mission to rescue the “lost sheep of the house of Israel.” In the ministry of Jesus Christ, God would embrace even those excluded by the law (prostitutes, tax collectors, prodigals, and sinners). For that reason, God’s own Son himself was excluded and violently killed. If the law, in the hands of those who are self-justifying, even with all its good intentions eclipses God’s promise in Christ alone, it must have its limits, and even its end (as both telos and finis). For Luther, Jesus Christ is the “greatest sinner” in that he bears the sins of us all. His death is the death of our sin. But his death is also the end of the law as accusation–Jesus’ resurrection places us sinners on a path outside the accusations of the law so that we might live by faith before God and before the world.

The gospel is itself not a “new law,” one which would be do-able since we have the “super-added gift of the Holy Spirit” to empower us. The gospel as grammar is not a directive at all, nor is it information about reality as such, nor is it a description of the landscape of our inner lives or spirituality. The gospel’s grammar is that of a promise (promissio), a commitment on the part of God to be for us (pro nobis). The Gospel, then, is not merely a way of incorporating gentiles into the covenant which God has already established with the Jews, as the “New Perspective” on Paul would have it. But as a “stumbling block” to the Jews and “foolishness” to the Gentiles it is the power and wisdom of God for both Jews and Gentiles who are equally guilty under the law, whether revealed as the Torah or discerned in nature (1 Corinthians 1:18-25).

That justification is forensic, a decree of acquittal, is often thought to be problematic. If it is a purely objective pronouncement of God’s favor to sinners for Jesus’ sake, then how are our lives changed? How does justification actually make a difference for peoples’ lives and in the world? Hence, how justification can somehow be “effective” is a matter quickly raised. In light of Luther’s critique one might suspect that this question arises from a concern to keep the human will intact and preserve the continuous existence of the person. That God’s forensic word is effective seems counter-intuitive. That it is effective can be understood only when we realize that this word of promise delivers the goods of forgiveness of sin, life, and salvation despite the fact that when we look at ourselves we still see sin. This word is the very in-breaking of God’s new era promised in the scriptures. The efficacy of the forensic word is not found in what we do to change our lives, but instead in how God’s word opens us up from the inside out so that we are not so concerned about ourselves, including our own salvation. Faith depends upon hearing God’s promise; it does not rest upon seeing its own improvement. Instead, free of such egoism, we can honor and love God for his own sake and work for the well-being of our neighbor and this good earth.

God’s justification of the sinner is decisively eschatological. In the resurrection of Christ, God imputes righteousness to the world for Jesus’ sake. But this imputation has two aspects. When God imputes righteousness to us, he makes us to be sinners at the same time. If we have been imputed to be righteous, it is only because we first have been condemned as sinners. In a sense, we are not only justified by faith–in trusting God’s promise of mercy to sinners–but in faith we also confess our own sinfulness. For it is not our own self-evaluation by which we can understand the depths of our sin but instead God’s own judgment of our lives. Justification is forensic, a decree, delivered as a message through a preacher: “You are found condemned and guilty before God’s law. You are a sinner and you bear the mark of death. But, for Jesus’ sake, you are forgiven and acquitted. He has borne your sin and death for you and has exchanged your loss with his own life.” The Christian life is not primarily a growth in righteousness-getting better at our efforts to be godly. Instead, God imputes ungodliness to all and everything human, including our very best, so that he might have mercy on all. Jesus’ cross is a judgment on us–and it judges not only our worst, but, ironically, our best. It was our best that sent Jesus to the cross. Our condemnation of him was on the basis of our best virtues, aptitude, and potentiality. This means, that for Luther, as for Paul, we are completely dead in trespasses and sins, and left with no basis for any self-justification whatsoever. Just as Christ, who knew no sin, became sin for us, we too are become thorough sinners in justification.

God’s justification of the sinner is decisively eschatological. In the resurrection of Christ, God imputes righteousness to the world for Jesus’ sake. But this imputation has two aspects. When God imputes righteousness to us, he makes us to be sinners at the same time. If we have been imputed to be righteous, it is only because we first have been condemned as sinners. In a sense, we are not only justified by faith–in trusting God’s promise of mercy to sinners–but in faith we also confess our own sinfulness. For it is not our own self-evaluation by which we can understand the depths of our sin but instead God’s own judgment of our lives. Justification is forensic, a decree, delivered as a message through a preacher: “You are found condemned and guilty before God’s law. You are a sinner and you bear the mark of death. But, for Jesus’ sake, you are forgiven and acquitted. He has borne your sin and death for you and has exchanged your loss with his own life.” The Christian life is not primarily a growth in righteousness-getting better at our efforts to be godly. Instead, God imputes ungodliness to all and everything human, including our very best, so that he might have mercy on all. Jesus’ cross is a judgment on us–and it judges not only our worst, but, ironically, our best. It was our best that sent Jesus to the cross. Our condemnation of him was on the basis of our best virtues, aptitude, and potentiality. This means, that for Luther, as for Paul, we are completely dead in trespasses and sins, and left with no basis for any self-justification whatsoever. Just as Christ, who knew no sin, became sin for us, we too are become thorough sinners in justification.

The core Lutheran insight about human nature is that our sin is best disclosed in that whoever we are, we are inherently self-justifying. This is why, if we would understand human nature aright, we must look to the doctrine of justification by faith. It alone discloses what it means to be human–one who is from the first and at the core–completely receptive, dependent on God for life. We are not primarily human in what we do or fail to do but to whom we are related and from whom we receive, God himself as the source of life. Our righteousness before God is a receptive life (vita passiva). A practical consequence of this reasoning is that we must distinguish who a person is–as one fundamentally related to God–from what a person does. In contrast to Athanasius (293-373), God became human not so that we might become divine, but so that we–through faith–might become human ourselves but with death behind us once and for all.

Dr. Mark Mattes:

“It is on the basis of God’s own vindication of his Son, who was himself without sin, but became sin for us and so was in the end justly accused as a violator of the Torah–God’s own law–that all sinners can have assurance of eternal life. In violating the law, Jesus Christ was faithful to his Father’s mission to rescue the “lost sheep of the house of Israel.” In the ministry of Jesus Christ, God would embrace even those excluded by the law (prostitutes, tax collectors, prodigals, and sinners). For that reason, God’s own Son himself was excluded and violently killed.”

I agree that Jesus was “justly accused as a violator of the Torah” because he became sin for us, but from this statement, Dr. Mattes seems to be saying that Jesus became sin for us primarily by actually violating God’s Law himself in that he embraced prostitutes, tax collectors, prodigals, and sinners. I would not only argue that this is not the primary way that Jesus became sin for us, but that it is not a way this happened at all! In Jesus’ trial he asks his opponents if they can accuse him of any sin and they remain silent. I think even the Pharisees realized, deep down, that Jesus was not violating the Torah, but fulfilling it and its meaning rightly – they just suppressed this knowledge. Paul points out how the “Law is good” but the problem is with us – though there are certain commandments of the O.T. Torah that make us uncomfortable, one must not forget that the Torah included moral commands to be merciful, and to love one’s neighbor as themself (so mercy was not just something related to the sacrifices).

Consider Numbers 35:31, which says: “Moreover ye shall take no satisfaction for the life of a murderer, which is guilty of death: but he shall be surely put to death.” In a lecture for the Maclauren Institute at the University of Minnesota on February 19th, 2005, (you can listen to the MP3) Walter Kaiser from Gordon Conwell, in the Open Forum on Difficult Old Testament Passages) pointed this passage out, claiming that it appears that a ransom (substitute, payment, retribution) could be accepted for all 19 of 20 the acts in the OT that deserve death (you know, homosexuality, disobeying parents, etc) murder being the exception, where no ransom could be accepted, because the value of human life is so great (image of God). Things seem a little bit more complex than you are making them.

Dr. Mattes, although I enjoy and appreciate much of what you write, I am perplexed by this your above statment, and am concerned that Martin Luther would not recognize it as representing his views on the [O.T.] Law of God, which is true and wise….

-Nathan

In your third post you say:

“For Luther, grace doesn’t perfect nature, elevating the finite to the infinite, but instead liberates nature, sets us free from ***our drive to control others***, our lives, even our own thoughts.”

Obviously, when we look at the O.T. Law we think about how this “drive to control others” (and worse) *seems* so very prominent.

But again, can we really say that “Jesus became sin for us primarily by actually violating God’s Law himself in that he embraced prostitutes, tax collectors, prodigals, and sinners”?

It seems to me that if we are going to understand Joseph as a righteous man, as the N.T. does, than we need to see that even the O.T. commands mercy, compassion, etc. – and that Joseph, who we know from Luke followed the O.T. Law, knew this. Hence Jesus’ actions in John 10 are understandable – and when Jesus asked his accusers who could accuse him of sin, they did not bring up this incident…

Looking forward to your response.

-Nathan

When I talk about the N.T. “understand[ing] Joseph as a righteous man” above, I am thinking about how this is the conclusion that comes from his not divorcing her, putting her away, and subjecting her to the possibility of stoning…

-Nathan

The law is true and wise, until it shockingly reaches it end in Christ, specifically in the death of Christ upon the cross, since it is written, cursed be everyone who hangs on a tree Deut 21:23. Christ did not become sin in his trial. He was innocent before his accusers. But at the cross the curse of the Lord came upon him and made him not a transgressor but the greatest of all sinners, David, Peter, Luther and all. Indeed, not just the greatest of sinners but sin itself. All of your statements about the types of worthy law that remain in the Scripture are true, until the cross. This is the logic from the cross, and apart from that, in this old world, the law remains in its entirety, not just in part, preserving life to some extent and accusing unto death. There the law is good, the law is holy, the law remains forever!

The fault is not the law, but it doesn’t have anyone else to convict once the cross of Christ ends this old world. Torah is a loaded word, and I take it, it refers to law, though in the Old Testament there are clearly promises given that are fulfilled in Christ. This is why Paul makes the proper distinction between Moses and Abraham, and between the Abraham of the covenant of circumcision and the Abraham that was made righteous by faith alone.

Pingback: J | Christian ● Lutheran ● Confessional