Several months ago, a colleague from my seminary days drew my attention to Johann Gerhard’s discussion of divine immutability in Volume Two of his Loci theologici (Exegesis), freshly released in English (On the Nature of God and on the Trinity, trans. R.J. Dinda [St. Louis: CPH, 2007]). The context was the question of how we can speak of God’s immutability in a Biblically responsible and theologically faithful way. While I appreciated what my colleague had to say, I also found it deeply problematic and decided to write a response.

Your responses to our exchange are also more than welcome!

I.

My colleague quoted the following passage by Gerhard:

“A rational nature can be changed in five ways. First, with respect to existence, such as if at some time it exists, at some time it does not exist. Second, with respect to place, if it is moved from one place to another. Third, with respect to accidents, if it is changed in quality or quantity. Fourth, with respect to understanding by the intellect, such as if one now considers true what he previously judged to be false. Fifth, with respect to the intent of the will, if one now decides to do something that he earlier had determined not to do” (§150).

My colleague then said that we should consider the consequences of denying these: “If you deny 1, you’re saying God could cease to exist, or at one time did not exist. And then He is not eternal. If you deny 2, you’re saying God is not omnipresent, and worse, that He is corporeal and can be pushed or blown around. And then He might not be present in all places to help and hear His people wherever they are. If you deny 3, you’re saying God could change the sort of God that He is – that He could get stronger or weaker, for example. And then He is not omnipotent. If you deny 4, you deny His omniscience, and have undermined the basis of His truthfulness, for one cannot be absolutely truthful if he can be surprised or learn something he previously was ignorant of. And if you deny 5? I think that would make God’s will fickle. Not only could He relent from destruction, He could also relent from mercy.”

My colleague asserted his personal belief in all the five ways, pointing out that they represented the position of not only Gerhard but also Augustine and Luther (though he was open to discussing this). He pointed out that Gerhard’s text includes Luther’s translation of Job 33:14: “When God once decides something, He does not afterward reconsider it,” together with Luther’s marginal note, “As a man after doing something ponders, regrets, and plans a change” (WA DB 10/1:71). This may be viewed as an affirmation of the fifth kind of immutability.

Finally, my colleague noted that this view of divine immutability neither bound one to a Calvinistic view of predestination, nor was it at odds with human free will. More importantly, my colleague wrote, immutability directly protected the doctrine of the Trinity, since it was an appreciation for divine immutability that had led the Council of Nicaea to affirm the eternal procession of the Son from the Father.

II.

This was my response:

While I appreciate your bringing Gerhard into the discussion, I can only sigh at how rationalistic this contribution is and how confused in its mixture of human speculation and biblical revelation.

1. METHODOLOGICALLY SPEAKING: The point of departure for Gerhard’s definition of immutability is the human being and the mutable ways of human existence. Each and every one of his definitions begins with human changeability only to deny it and then project the result onto God. Now, whether this speculation is actually able to embrace God is another story. So what we end up with is a “god” made to man’s measure and expressing our own god-making flights of fancy.

How and by what right can we be sure that the immutability we’ve speculatively arrived at on the basis of our own mutability is God’s immutability, and not our own pious wishes? How can we be sure that God will even fit into the straightjacket of divinity we’ve prepared for him, ostensibly for the sake of safeguarding his divinity? This situation is hardly helped by supplying an already-made definition with an a-contextual sprinkling of biblical texts.

It is God himself who defines his immutability! He is the Lord even of his immutability – however unbefitting of the divine the latter may in the end seem to us!

2. A couple of remarks on how constraining these definitions of (im)mutability are:

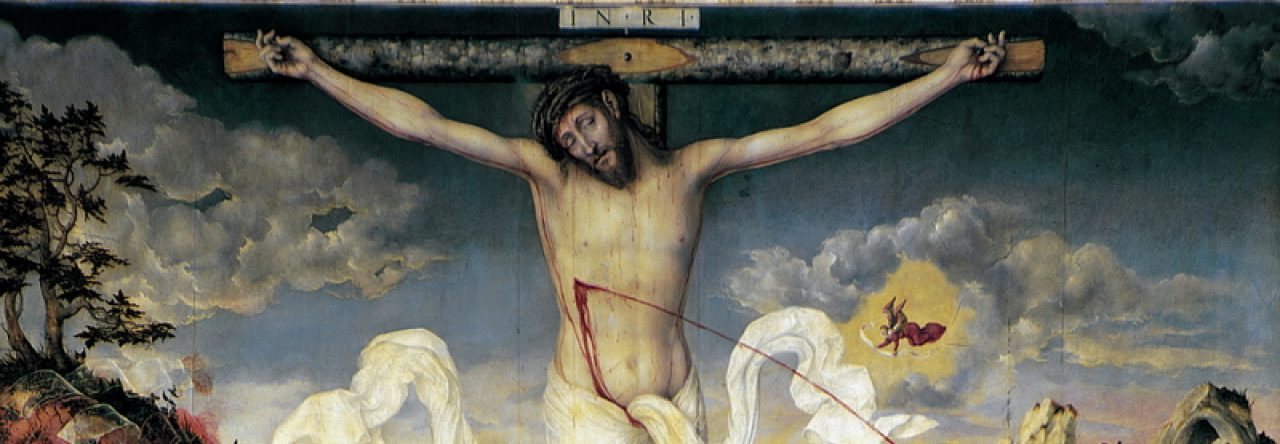

– regarding EXISTENCE: how do we know that the character of God’s existence is conceptually derivative from our existence? I’m not so sure that God exists in the way we exist. I’m not even sure that rationally we ourselves can know what it means for us to exist, let alone for God, for even in the case of our existence it is not a question of a rational definition but one that involves the realities of nature and grace, sin and faith. Finally, how do we deal with God’s own death (the “Gott selbst ist tot” of a certain Lutheran chorale), once we’ve thrust him into this straightjacket of sublime existence (for which, by the way, the article of his Tri-unity is only an irrelevant afterthought)?

– regarding PRESENCE: how do we know that God’s omnipresence is simply a denial of our moving from one place to another? The biblical witness nowhere leads one to understand that God is simply uniformly present everywhere, as if he couldn’t help himself, but rather that he is free to be present in various ways in various created realities. Perhaps it would even be proper to say that God has the world present to himself, rather than being simply present in it, as if he occupied space (the way we do).

– regarding DISPOSITION: while remaining fundamentally faithful, fundamentally loving, fundamentally self-same, does God not – precisely on account of this ethical self-sameness – change in his relationship to the world: does he not repent and relent, listen to prayer, withhold his wrath, accept sacrifices; is he not pleased or displeased, jealous or propitiated? Does the cross have no impact on him? (contra Gerhard who says: “Therefore because of this simplicity of essence, He cannot receive the action of anything,” p. 157). The verbal and philosophical acrobatics that Gerhard engages in are pretty much tantamount to throwing the Bible out of the window, or at best regarding it as radically misleading in the way it speaks of God.

You quote Luther’s version of Job. 33:14: “When God once decides something, He does not afterward reconsider it.” In the margin [Gerhard] adds [following Luther]: “As a man after doing something ponders, regrets, and plans a change.” – One can wonder, more fundamentally, whether Gerhard’s “god” can even make decisions about anything ad extra at all. How fundamentally wrong Gerhard is is revealed by his statement: “because of this infinity nothing can act upon Him, because all things besides God are finite, which cannot act upon the infinite” (p. 157). I guess this is Gerhard’s own version of finitum infiniti non capax est. Yet it does not seem to occur to Gerhard that perhaps, precisely on account of his independence, more than that, on account of his love, God can allow himself to be affected by the finite, perhaps because on a level even more fundamental, which Gerhard does not explore, he remains who he is, faithful and loving. It is as significant, as it is unchristian, that Gerhard says God cannot be affected in his relationship to creation because of his simplicity and infinity. Sigh.

3. It is interesting that Gerhard’s definition includes the ethical only as an afterthought, privileging instead God’s ontological qualities: omnipotence, omniscience and omnipresence (simplicity and infinity). But these might just as well be predicated of a total monster, there’s nothing inherently divine in them, especially when they are derived from our own speculative consideration of ourselves.

Don’t get me wrong, I do not wish in principle to deny these concepts in reference to God. I’m merely pointing out that by themselves they are a-trinitarian and a-biblical, and so do more harm than good. They need to be given a center, and that center is the loving relationship between the Father and the Son in the fellowship of the Spirit. Only as the omnipotence of God’s love does omnipotence make sense in a Christian and biblically responsible way (and we should allow ourselves to be surprised by it, as well as allowing our prior concepts of omnipotence to be thwarted by it); only as the omnipresence of God who in himself is loving self-relatedness does omnipresence make sense; only as the omniscience of a loving God does omniscience make sense as the omniscience of the One who knows us inside out and yet (!) loves us.

I find it astonishing that you think that by itself immutability (and its rationalistic corollaries, omnipotence, omniscience, omnipresence) can assure the integrity of the creed of Nicaea. I have always thought that the Triune nature of God is assured by the fact that he reveals himself not merely as loving but, from eternity to eternity, as Love, love between the Father and the Son through their Spirit.

In the end, I do not, of course, wish to deny divine immutability. Immutability, as a doctrine, was originally developed in the interest of soteriology, as a doctrine of the self-sameness of God’s love, and his faithfulness that none and nothing can undermine. Gerhard’s example shows how easy it is to lose sight of that and to get carried away. God may, in fact, be closer to us than the soaring of our “benumbed conceiving.”

Piotr Malysz

Dear Piotr,

Thanks for not naming me as the target of your diatribe. ;-) I look forward to seeing what you have to say about Gerhard’s forthcoming Locus 4 (1625 Exegesis), “On the Person of Christ.” Maybe you could see Gerhard’s presentation on the Nature of God as the thesis, and On the Person of Christ as the antithesis. Gerhard certainly does not think of God as a monster–that’s abundantly clear in all of the “practical use” sections of the entire Theological Commonplaces.

On divine immutability and the patristic doctrine of the Trinity, I would not say that “by itself” immutability can assure the integrity of the creed of Nicea. However, immutability is one component part of the the background of the trinitarian faith of the fathers who set forth the creed of Nicea.

I acknowledge your concerns about natural theology, the seeming inconsistency of the classical Christian doctrine of the immutability of the divine nature with Bible narratives like Exod. 32:14, with the doctrine of human free will, and the doctrine of the person and work of Christ (unitive Christology, “O deepest dread, our God is dead,” –Lutheran Service Book 448:2–etc.).

My concerns are these:

* I think there needs to be room for natural theology in Christian theology. Even from revelation (Rom. 1) we know that natural theology can lead us to some true (though non-salvific) knowledge of God. Rom. 1 makes clear that this natural knowledge of God can inform people of God’s existence, power, and divinity. We shouldn’t get uncomfortable with the thought that natural theology could tell us something true about God.

* Because there is such a thing as true natural theology, it doesn’t surprise me if some pagan philosophers such as Plotinus and Proclus have discovered some true things about the God’s nature. (Nota bene: I’m not saying they got it *all* right or even mostly right. I’m just saying that, if they said something, that doesn’t make it automatically false.)

* Regardless of whether or not any pagan philosophers rightly understood divine immutability, there are indeed a number of Bible passages that state this in various ways. Of course, then there are other narratives in the Scriptures that speak of God changing His mind. So one must reconcile the two (if one believes the unity of Scripture and the primary divine authorship of Scripture, as I do). I’d prefer not to limit one or the other, for example, “God is only immutable in his love, but in His will (or even essence!) He is actually changeable.” Limitation does not seem to fit with the categorical statement of St. James 1:17 “no variation or shadow due to change.” If God is eternal and omniscient, then He must eternally know what He will say and do. From our perspective in time, it appears that God changes His mind. Yet He is not surprised by our actions. (If by “mutability,” one simply means that at one time God says or relates to me in one way, and at another time, he says something or relates to me in a different way, then I have no problem with calling that “mutability,” but I doubt that that’s how the fathers of the church have used that term.)

* I have not seen any orthodox theologian before the 20th century that would deny the immutability or impassibility of the divine nature. This includes Luther. Nevertheless, if you know of passages where Luther says the opposite, I would be happy to be corrected.

* The Formula of Concord confesses the immutability of God’s will. FC SD IV: 16: “When this word ‘necessary’ is employed, it should be understood not of coercion, but only of the ordinance of the immutable will of God, whose debtors we are”. V: 17: “the Law is properly a divine doctrine, in which the righteous, immutable will of God is revealed”. VI: 15: “when we speak of good works which are in accordance with God’s Law (for otherwise they are not good works), then the word ‘Law’ has only one sense, namely, the immutable will of God, according to which men are to conduct themselves in their lives.” VI: 17: “But when man is born anew by the Spirit of God . . . he lives according to the immutable will of God comprised in the Law”. I find it interesting that it is precisely the Law which is said to be God’s immutable will by the fathers of the Formula of Concord.

* This underlines the necessity of Christ to fulfill the Law for us. God could not simply change His mind or change the Law. The price had to be paid by man, and that’s what Christ did for us. So immutability of God’s will (that is, His truthfulness) plays a foundational role in the classic doctrine of the atonement, such as that set forth by St. Anselm (Cur Deus Homo) and St. Athanasius (De incarnatione).

* A big concern of mine is what happens with God’s eternity and truthfulness if His immutability is undermined.

So here are a few questions to contribute to the conversation:

* What do you (not just Piotr, but all Lutherans reading this blog) think of open theism? What do you think of process theology? (These are two modern theologies that deny divine immutability to one extent or another.)

* What church fathers ever denied divine immutability in the way that Gerhard sets it forth? (I feel this question is important from the standpoint both of the 4th commandment, and of the Lutheran Symbols, such as AC XXVI 35, XXI 5, etc.)

Thanks for the very interesting blog. I wish you all much joy and peace as you continue to stimulate us all.

Cordially,

Rev. Benjamin T. G. Mayes

Divine immutability is the theological ground for the unconditional character of the Gospel. By extension, it is the basis of assurance for sinners convicted by the Law in its accusing function. So that as an abstraction (in all its radical hiddenness vis-a-vis Deus absconditus), it cannot be explained away, but can only be concretely proclaimed in the Gospel as the electing will of God for bound sinners.

How about this: What always seems to be the challenge to God’s immutability is love itself.

That is, it is only through love that we can explain: The creation of time itself; The creation of man; The “interaction” between the Triune God; God enterinig “our” time through the incarnation, life, death, and resurrection of Christ; What seems to be God’s changed mind; As you’ve put it: “Does he not repent and relent, listen to prayer, withhold his wrath, accept sacrifices; is he not pleased or displeased, jealous or propitiated? Does the cross have no impact on him?

Can God’s (immutable) essense as love explain all those things that seem to us to be his mutability?

Just some thoughts. I may be way off track.

This is a little like listening to a high medieval debate between Dominican Thomists and Franciscan Nominalists…

I was telling Dr. Tanis the other day that I have personally never caught the “no natural theology” “no analogy of being” bug because I think that our primary categories for thinking through these issues should be “hidden vs. revealed” and “law vs. gospel” not “reason vs. revelation” or “the analogy of faith (in Barth’s sense) vs. the analogy of being.”

A couple of things should be said about Gerhard’s treatment.

1. What Gerhard (and Lutheran scholasticism in general) says in my view actually does presuppose God as he is adduced from the concrete Biblical narrative . Each of the reasons that Gerhard gives seem to me to be implicit in the Bible. If God is the God of the gospel, he most certainly cannot change and all the other omni’s must be valid too. If he were not immutable, then the gospel would not be true because it would not be an immutable promise grounded in his immutable being and his omnipotent power to fufill anything he promised (See Luther in “Bondage of the Will”). This being the main theme of the Bible, it must govern our reading of the Bible. That the Bible some times says things like “God changed his mind” cannot be played off against statements that insist on his immutability. Beyond the fact that the gospel should govern our reading of Scripture, it is logically very difficult to deal with statements of the Bible that teach immutability if we assume mutability of the divine being. In other words, it’s easier and more logical to say that statements that teach mutability are figures of speech than it is to explain why God does really change when he states in certain places that he doesn’t.

2. The death of God in Christ should not be an issue. Within classical Lutheran Christology (I not only refer you to Chemnitz’s “The Two Natures in Christ”, but also Luther in the “Disputation concern the Word made Flesh”), the divine nature does not some how blip out of existence with Jesus’ death on the cross. According to the Genus Apostelisticum (did I spell that correctly?), considered in the concrete the divine nature receives the action what happens to the human nature since due to the hypostatic union it is one theandric subject. This does not mean that it affected in its immutability anymore than my nose would be affected by me hurting my toe- nevertheless, “I am hurt” not just part of me.

Modern attempts have been made to suggest that the divine nature some how is mutable becuase of the death of Jesus. The problem with this is that this all presupposes exactly the opposite of what Luther was suggesting in the theology of the cross. The modern German Protestant interpretation of the theology of the cross is that the cross is an epistemic foot hold that we have to “see” the divine being. This is superior to the supposedly philosophical foothold of classical theism because we can now “see” what God is on the basis of what happens in the cross- namely that he can suffer and is mutable. Luther didn’t believe this though. We “suffer” God in Jesus under his opposite (Bayer). In other words, God really is all the omni’s- he hides these omni’s under the weak and suffering person of Jesus in order to reveal to us our sin and confound our intellects so that we will become passive and receptive in faith. He “hear” and therefore “suffer” the divine being, we do not “see.” To “see” who God is precisely the opposite of this, namely it is the theology of glory- modern theologies of the cross (Jungel and Moltmann come to mind) are therefore actually theologies of glory. They are what Gerhard Forde called “Negative” theologies of glory because now we “see” that God is weak and suffering. Seeing demands corresponding and therefore we should work for socialism or whatever. The cross becoimes a new ideal. In other words, the whole thing makes the cross a new law (Jungel even does this at the end of his justification book- which was very disappointing!)

3. There’s nothing particularly wrong with natural theology in of itself. I have no problem with agreeing with St. Paul in Romans 1 that we can know a great deal about God from the creation and that there is much validity to the analogy of being. The problem is that analogy is always law. In other words, if God being is presented to us as it is in itself, then I am always placed under demand: “I am just, now conform to my justice, etc.” The revelation of God’s being through analogy presupposes that God echos his being in such a way that he does not surrender it to us. It present his reality standing over against us and therefore asks us to conform. God in the gospel surrenders his being to us and gives us the fullness of his reality in Christ (Genus Majesticum) and then in Word and Sacrament. He does not echo his being in these things, but donates the fullness of his reality to us by surrendering it to us as promise. Promising is always self-donation. Therefore he does not remain in continuity with himself, but by changing his relationship to us, breaks with his old reality as law. Therefore, does analogy of being work? Yes, but it’s not the reality of God as we find him surrendered to us in the gospel- so we can gain valid knowledge of God this way, but it will always be condemning knowledge.

Part of the problem with modern German theology is that it has been so tied to Kantian metaphysical assumptions that it confuses issues. Gaining knowledge of God apart from the Bible isn’t bad because it’s some how the wrong epistemic starting point or because it violates God’s lordship to be naturally knowable. Rather it’s bad becuase it’s always law. God should be all the omni’s, but if they’re not the omni’s used pro nobis, then he is nothing but a consuming fire to us (the Heidelberg Disputation does deny natural knowledge of God, it just says it’s not useful for salvation!). Furthermore, this God cannot be explained away by epistemic theories about divine mutability or general graciousness either. This God of analogy who is a consuming fire is most certainly real- the God of the gospel presupposes this. We would not need the God of the gospel if God outside of Christ did not persist as the God of analogy and law.

Jack’s exposition above is very helpful. I have been doing a little reading on By Faith Alone in honour of the late Dr. Forde, and one of the essays which was written Dr. Strohl makes the point that unlike Calvin, for Luther, hearing is pre-eminent.

Dear Jack,

Sorry for the late reply. I’m on a field assignment in Singapore. I’m based at University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur. Let me give you my email; I hope you don’t mind emailing me first. It’s at jasonloh@um.edu.my

I’m a fan of Gerhard Forde, and I own all his published works (to my knowledge). Oh yes, except the ones which are published as chapters in books like Trinity, Time and the Church and something, essays in honour of Robert W. Jenson, his essay on the ministry, another book which I do no remember. I have also recently acquired By Faith Alone. I also share your reservations and cautious approach in receiving Forde’s doctrine of the atonement. Even I though I appreciate the modern reappropriation of the Luther Renaissance, I subscribe to model of inspiration (re: Scripture) as held by Lutheran Orthodoxy. Where I would differ would be in the area of the Law as a lex aeterna, where I agree with Luther’s view that the Law is essentially existential and temporal.

Thank you for your attention, and I look forward to hearing from you soon. In the meantime, I’ll try to access the Wittenberg Trail too.